The Wonder of Cloisonné

What is Cloisonné?

Cloisonné is a centuries-old technique for decorating metal objects by creating intricate designs with colored materials such as enamel, gemstones or glass. Thin metal strips, usually made of gold, silver or copper, are soldered or glued to the surface to form small compartments or cloisons (from the French word for "partitions"). These compartments are filled with colored material, traditionally glass or gemstones, and in modern times, enamel, which is then fired at high temperatures. The firing process makes the enamel hard and durable, resulting in a glossy, smooth surface. Cloisonné is prized for its rich, luminous colors and intricate, often symmetrical patterns. The technique has been used in many cultures, including ancient Egypt, Byzantine, Chinese and Japanese art, each contributing its own stylistic nuances and technical innovations.

Related Techniques

Cloisonné and champlevé are two enamel techniques used to create decorative designs on metal surfaces. Cloisonné, a technique especially popular in Europe until around 1000–1100 AD, involves soldering thin metal strips onto a base plate to create compartments, which are then filled with enamel. By contrast, champlevé, which gained prominence in the medieval period, involves carving or etching recesses into a metal surface, typically copper, which are then filled with enamel. It was less expensive to produce, as gilding was only applied to the exposed metal. By the 1400s, painted enamels overtook both techniques, offering a way to apply enamel directly to metal surfaces for more intricate designs. Around the same time, plique-à-jour, which involves creating translucent enamel designs without a backing, gained popularity for its stained-glass effect.

The History of Cloisonné in the West

In ancient times, cloisonné was used primarily to decorate jewelry and weapons, often featuring thick cloison walls and mostly adorning small objects. Varieties of the technique are believed to have been developed simultaneously in both ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt before 1800 B.C. In Egypt, cloisonné designs were characterized by thick gold walls and small compartments, which were filled with gemstones like turquoise, lapis lazuli, carnelian and garnet, as well as glass paste. This paste, faience, was similar to enamel but not fully melted, as the gold used for the cloisons could not withstand the high temperatures needed to melt the glass fully. Notably, King Tutankhamun's tomb contained several pieces of cloisonné jewelry, showcasing the technique's prominence in ancient Egyptian craftsmanship.

At Sutton Hoo, the site of a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon ship burial in Suffolk, England, craftsmen used cloisonné to create stunning designs, usually with garnet inlays and sometimes combined with enamel. Over time, some of the artifacts have lost their original gems or glass inlays, making it difficult to fully assess their original appearance. In some cases, the glass used was so thin that the intricate gold patterns beneath were visible, adding a layer of depth and complexity to the designs. This technique showcases the high level of craftsmanship in early medieval Anglo-Saxon art.

In Byzantine art, cloisonné techniques evolved to use thinner wires, allowing for more intricate and detailed designs, often depicting religious icons. By this time, enamel had become the primary material used to fill the compartments, though garnets were also commonly incorporated, as the gemstone symbolized the blood of Christ in Christian iconography. The detailed cloisonné work produced in the Byzantine Empire had a significant influence on neighboring cultures, spreading to the so-called "barbarian" tribes of Europe, where the technique was adapted into their own artistic traditions.

Carolingian and Ottonian art in Europe drew significant inspiration from Byzantine techniques, particularly in their use of cloisonné. However, during the Renaissance (14th-17th centuries), artists in Europe transitioned primarily to champlevé methods for their enamel work. This period also saw the flourishing of Chinese cloisonné, with artisans creating exquisite bowls and vessels that showcased vibrant designs, especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties. By the 1700s, these Chinese techniques began to spread to the West, influencing various artistic traditions. In the 1800s, Japan also adopted similar methods in pottery and ceramics, further enriching the art form. In modern times, traditional cloisonné techniques have evolved to include materials like lacquer and acrylic fillings, while contemporary applications, such as the BMW logo, utilize a champlevé technique reminiscent of traditional cloisonné.

The History of Cloisonné in China

Cloisonné made its way to China through influences from Byzantium and the Islamic world, with the first reference to this technique appearing in 1388, described as “Dashi ware," “Muslim ware” or even “Ware from the Devil's Country"—any place west of China. Even though very few surviving pieces from the 1300s exist, the earliest surviving cloisonné piece, which dates to the 1400s, showcases considerable technical expertise, indicating a long tradition of cloisonne in the region. Initially, in the 1300s, cloisonné was considered too flamboyant for serious settings, deemed appropriate only for women’s chambers. The most elaborate and valuable pieces emerged during the Ming Dynasty, particularly in the 1400s.

In Chinese cloisonné, blue is the most prominent color, and there are notable stylistic differences compared to Byzantine cloisonné: the wire does not always enclose just one color, serving sometimes as an additional decorative element, and in some instances, no wire separates two colors. Initially, Chinese artisans applied cloisonné to metal objects like brass or bronze vases, later expanding to porcelain.

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) is celebrated as the golden age of Chinese cloisonné due to several key factors that enhanced the quality and artistry of the pieces produced during this period. Technological advancements allowed artisans to master the firing process, achieving vibrant colors and intricate designs with minimal imperfections. Access to high-quality materials, such as refined copper and a wide range of vibrant enamels, further elevated the craftsmanship. The era's cultural revival fostered artistic innovation, with craftsmen experimenting with new motifs inspired by traditional Chinese themes like flowers, animals and celestial imagery. Highly skilled artisans, trained in traditional methods, specialized in various aspects of production, ensuring a high standard of quality. Royal patronage from Ming emperors, who valued cloisonné as a decorative art form, provided resources and encouragement for innovation. Additionally, the cultural significance of cloisonné items, often representing prosperity and good fortune, motivated artisans to produce their finest work. The combination of these elements led to some of the most exquisite examples of cloisonné in history, making Ming Dynasty pieces highly prized by collectors and influential in the development of modern craftsmanship.

The decline in the quality of Chinese cloisonné during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) can be attributed to several factors, including the overproduction of items, a shift in artistic standards and the rise of mass production techniques. As demand for cloisonné increased, especially among Western markets, artisans often compromised on craftsmanship in favor of quantity, resulting in less intricate designs and lower-quality materials. The techniques that had once set Ming cloisonné apart were diluted, leading to a decline in the overall aesthetic and technical excellence of the pieces. However, despite this decline, Chinese cloisonné gained significant international recognition, exemplified by its success at events like the 1893 Chicago World's Fair and the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, where it was awarded first prize.

The History of Cloisonné in Japan

Cloisonné began in Japan around the 8th century BC, influenced by techniques from Greece and Egypt, with early uses primarily serving religious purposes. By the 17th century, cloisonné gained popularity among the common people, leading to the production of small everyday items. The period from 1890 to 1910 is often regarded as the golden age of Japanese enamels, during which the Ando Cloisonné Company emerged as the leading producer. Japanese cloisonné earned numerous prizes at international exhibitions, reflecting its superior craftsmanship and innovation. The distinctiveness of Japanese cloisonné lay in its new designs and vibrant color palettes, which set it apart as the finest in the world during this period.

The History of Cloisonné in Russia

Cloisonné in Russia has its roots in the 9th to 13th centuries when the technique was introduced from Byzantium. However, its practice came to a halt during the mid-13th century with the Mongol invasions. By the end of the 14th century, Russian artisans began utilizing champlevé techniques instead. The 19th century witnessed a revival of cloisonné styles, particularly through renowned jewelers such as Peter Carl Fabergé and Mikhail Khlebnikov. Fabergé's approach featured wire shapes akin to traditional cloisonné, but instead of filling the spaces with enamel to create a flat surface, he painted the enamel on, allowing for a more textured and dynamic appearance. This innovation contributed to the uniqueness of Russian cloisonné during this period, blending traditional methods with artistic experimentation.

Cloisonné Techniques

In modern practices, artists often use copper as the base material due to its affordability, lightweight nature and ease of manipulation, though gold and silver are also utilized. The wires employed in contemporary cloisonné are typically made of fine silver or gold, bent at right angles. Unlike earlier methods, modern techniques largely avoid soldering, as it can lead to discoloration and bubbling over time. Instead, a thin layer of enamel is fired over the base, adhering to the metal without the need for glue, which burns off during the firing process. This firing occurs in a kiln, where the enamel sinks down, necessitating multiple refills and firings until the overall surface is level. Cloisonné can be crafted in three styles: concave, convex and flat, each offering a unique perspective on this intricate and colorful art form.

Making Cloisonné Beads

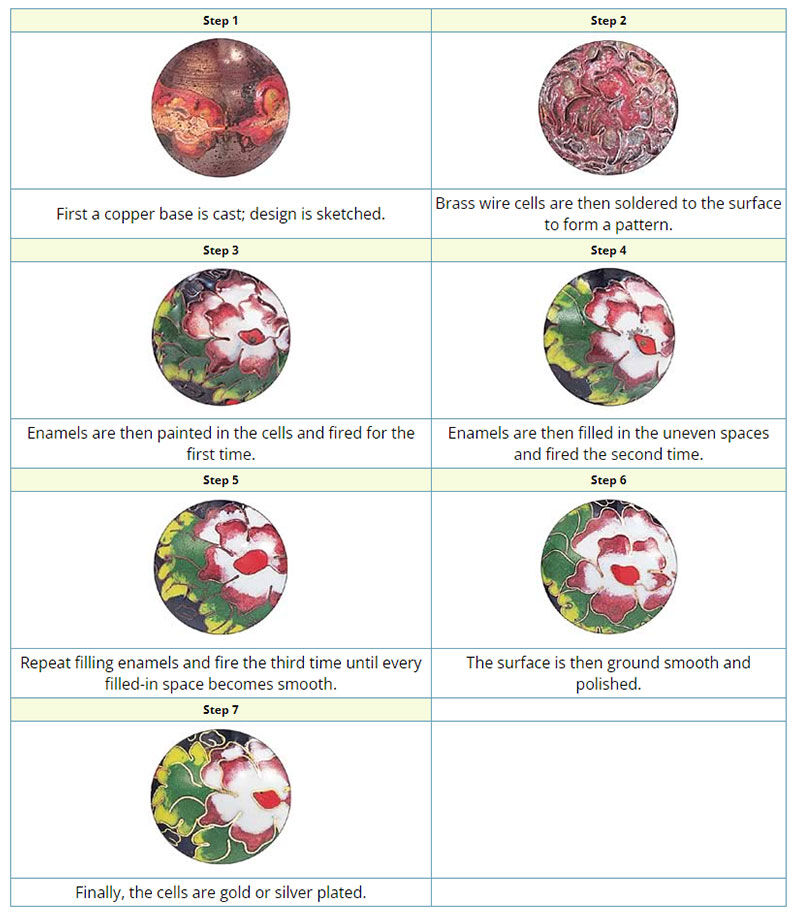

Cloisonné beads are created by skilled artisans. Each cloisonné bead can take up to four hours to produce. Dozens of tiny cloisons are soldered to the bead's surface, then filled with four layers of enamel and fired after each filling. Then each bead is polished, revealing intricate and beautiful designs. Since each bead is handmade, colors and styles may vary.

Caring for Cloisonné:

To maintain the beauty and integrity of your cloisonné pieces, follow these care guidelines. Cleaning should be done regularly by dusting with a soft cloth; avoid using water, but a slightly damp cloth is acceptable for light cleaning. Always clean your pieces before storing them to preserve their quality.

Storage is crucial—store your cloisonné in a protective case or wrap it in cushioning material to prevent damage. Keep the pieces in a cool, dry place, avoiding direct sunlight to prevent fading and ensuring there are no significant fluctuations in heat or humidity, which can lead to cracking. By treating your cloisonné gently and following these guidelines, you can help ensure its longevity.

Cloisonné is a rich and vibrant art form with a history that spans continents and centuries. From its ancient origins in Mesopotamia to its modern interpretations around the globe, this technique has evolved while retaining its fundamental beauty and craftsmanship. The various styles and methods that define cloisonné showcase intricate designs and brilliant colors, which not only please the eye but also tell a story of cultural exchange and innovation. Understanding the history and techniques of cloisonné enhances appreciation for this exquisite art form.

Want to dive deeper into cloisonné? Check out this FREE video featuring Doreen Stephens as she demonstrates the cloisonné process, showcasing how to create beautiful beads, pendants and artistic objects.

Shop Fire Mountain Gems and Beads' selection of cloisonné beads to include these stunning pieces in jewelry designs.

Shop for Your Materials Here:

Have a question regarding this project? Email Customer Service.

Copyright Permissions

All works of authorship (articles, videos, tutorials and other creative works) are from the Fire Mountain Gems and Beads® Collection, and permission to copy is granted for non-commercial educational purposes only. All other reproduction requires written permission. For more information, please email copyrightpermission@firemtn.com.